BUFFALO SONG by Joseph Bruchac and illustrated by Bill Farnsworth tells the story of the efforts of Samuel Walking Coyote, Whista Shinchilapi, to save the buffalo, an animal sacred to Native Americans. The vast herds of buffalo that once roamed across North America had been decimated. Rescuing one animal and then another, Walking Coyote and his family established a new fledgling herd on the Flathead  Indian Reservation in Montana.

Indian Reservation in Montana.

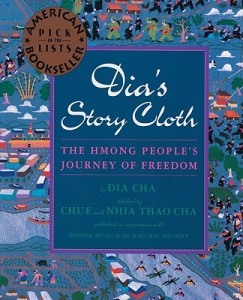

DIA’S STORY CLOTH: THE HMONG PEOPLE’S JOURNEY OF FREEDOM by Dia Cha, stitched by Chue and Nhia Thao Cha and published in cooperation with The Denver Museum of Natural History. Become immersed in a beautifully described unfolding of family history. The Hmong story is stitched with words and images. Look in the Tool Box for an activity to share with students.

MY PAPA DIEGO AND ME: MI PAPÁ DIEGO Y YO ,  recollections by Guadalupe Rivera Marin, artwork by her father, Diego Rivera.

recollections by Guadalupe Rivera Marin, artwork by her father, Diego Rivera.

What a beautiful book! With each art piece from her father’s work, a daughter tells stories about her artist father and the children in his paintings. In Spanish and English, the pictures and words express the delight and love between father and child, while presenting aspects of their beloved home.

The bilingual picture book, MY ABUELITA, by Tony Johnston, illustrated by Yuyi Morales with photographs by Tim O’Meara bounces with energy and color. The playfulness between grandma and child celebrates family. Listen in as Abuelita shouts: “Being round gives me a big round voice!” All the better to tell my big round stories.

CLOUD TEA MONKEYS by Mal Peet and Elspeth Graham, illustrated by Juan  Wijngaard.

Wijngaard.

Words and images sweep you into the mystical tea hills of northern India. Mal Peet, Elspeth Graham, and Juan Wijngaard have created a magical story of little Tashi’s courage and persistence – and faith in goodness and monkeys – all put together to enable Tashi to save her family, her mother. For fun, as part of the authors’ note, we are told that “you can still buy “monkey-picked tea,”  though whether or not it is really picked by monkeys is another story again…..”

though whether or not it is really picked by monkeys is another story again…..”

SALTYPIE: A CHOCTAW JOURNEY FROM DARKNESS INTO LIGHT by Tim Tingle, illustrated by Karen Clarkson. “American Indians are the least understood and the most misunderstood of us all.” Tim Tingle uses this quote from John F. Kennedy (1963). Perhaps even more misunderstood are American Indian families. Enjoy this delightful memoir told by and about one of the best storytellers, Tim Tingle.

Extend the reading with more information on the book HERE.